News

Santiago Formoso in Conversation (Part I)

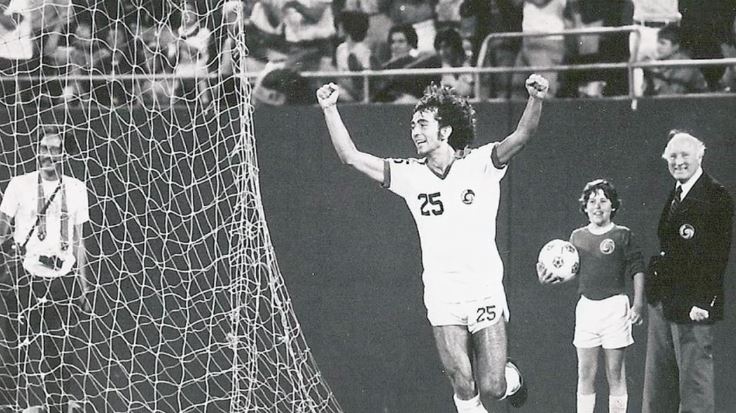

Santiago Formoso spent two seasons with the Cosmos, beginning with the 1977 postseason world tour, scoring twice in 46 league appearances from his left back position. The speedy, stylish and notoriously sleepy-headed left back was a product of the local soccer scene, graduating from Kearny High School in 1973 before playing at the University of Pennsylvania and beginning his professional career with the Hartford Bicentennials in 1976. Few knew the US National Team standout was a native of Vigo, Spain in the Galicia region of northwest Spain.

The documentary film, Alén do Cosmos (written and directed by Pedro Pablo Alonso) tells his story. After a premiere in Vigo last year and screenings at the Thinking Football Festival in Bilbao and the Off Side Festival in Barcelona, Alén do Cosmos makes its New York debut at the Galician Cinema and Food Festival at 6:00pm this Thursday, June 29th, at the Cervantes Institute, 211 E. 48th St. in Manhattan.

Santiago recently took time to discuss the film and his career with Club Historian Dr. David Kilpatrick.

Dr. David Kilpatrick (DK): I always thought of you as living the American dream – the local kid from Kearny playing with the Galácticos of the Cosmos. But this documentary really taps into not only your Spanish identity, but your identity as a Galician – even the title of the film, Alén do Cosmos, is in Galician dialect.

Santiago Formoso (SF): I almost felt like a Kearny guy myself, really, because I came so young. I came as a 16 year old, although I moved into the Ironbound section of Newark first. And then moving to Kearny I just totally assimilated the culture, you know. I blended right in so everyone just thought I was from Kearny; they never assumed I was European. But I think that had a lot to do with the fact that right from the get-go I was playing for the New Jersey state youth team with Hugh O’Neill, Bobby Smith – great American players, traveling along, up and down the east coast. Manny Schellscheidt was the coach. They really took me in like I was one of them and that’s what gave me the heads up on everything. Although my English wasn’t that good at the time 'cause I was a new arrival, but I totally assimilated into the culture and never looked back.

DK: The film actually takes you back to your roots in Vigo.

SF: Yes, we filmed it on both sides of the Atlantic. The reason why was because, first of all these are my roots, where I came from, my neighborhood, my friends, the kids I played ball with, that kinds of stuff. This movie is about “here is a Galician player for the New York Cosmos and nobody knows about it”. I went unnoticed because everybody assumed because I was on the Olympic Team and the National Team that I was a local kid from Jersey.

DK: That’s what I always thought.

SF: And I wasn’t. Not that I wasn’t, soccer-wise I guess I was, because I pretty much grew up here playing ball, but I was born on the other side. So that’s what totally fascinated them because they’re looking at the most iconic team from the ‘70s – the most well-known team at the time – and they say, “What, a Gallego playing on the team?” You know, We didn’t pick it up, and they, the journalists were more confused than anybody else, they said “How come no one picked it up?” I remember when we played in Madrid at one time that there was a big article in the paper but that was the only time I ever saw anything. So I used to go home every summer to Europe and go totally unnoticed. At the time my friends my age were in the military or they were engaged, getting married, that kind of stuff. I used to go home and go incognito. I wasn’t going around going “I played for the US Olympic Team,” I wasn’t that type of kid. I would just go there, visit my family, spend time with my family, go to the other side. I’m also half-Basque (my mother’s side is Basque), so I used to go to the other side, to San Sebastián. And my family’s totally not sports-people. So they never said, “Oh, my son plays for the New York Cosmos.” No, they were not that type. They were like, “Oh yeah, he’s in America, he emigrated, he plays soccer – we’re not sure yet.”

DK: Santiago, I always thought you were Scottish.

SF: Yeah, with a name like Santiago, right.

DK: Growing up in Kearny, though.

SF: That was the other side of the coin, too. Being that it wasn’t Kearny today, forget it, it’s all Peruvians and whatever, but in my days I think there were like three Spanish families in town, that’s about it. So no one even knew where Spain was. They thought Spain was like south of Mexico or something like that.

DK: Were you conscious of your Spanish or Galician identity on the pitch?

SF: No. No, no, no.

DK: So it was more just really that you were lucky to be living in a soccer hotbed like Kearny.

SF: Exactly. And it wasn’t done on purpose. When I first came Newark East Side had a great team. And that’s where I played my freshman year. Then, you’ve gotta remember Newark at the time, it was right after the riots. So they were busing the kids and all that. I called my parents and said, “What the hell are we doing? Where did we move to?” Because I come from a pretty big city, Vigo for European standards, was a pretty big city and I was a city boy. I had another different vision of what America was like. So, I had a younger brother, I still have him, five years younger than I. My father at the time was working at the Woodmere Country Club out on the Island, this is where the Kennedys had their membership at the time. He was the chef there. And my brother worked at the golf course. He came with him in ’65 or something like that. We were living in Jersey, so they would come over on the weekend. Then we said, “We’ve gotta get out of here.” The people that we lived with were also Gallego. My father had like a distant cousin or something like that lived in Kearny. So he said, “Oh I can get you, one of our friends who has a home in Kearny, we’ll see if they have any room available,” and that’s how we moved to Kearny, not knowing it was a popular [soccer] hotbed in Kearny. For me, I walked into [...]. The funniest part, I wasn’t really thinking soccer was gonna make it in this country or that that was my future. So when I got to the high school, at Newark we had beat Kearny the year before. I didn’t go to preseason or anything, I just showed up in school.

They said I needed to go to a tryout. “You go with the JVs,” the coach said. I said, “Okay, whatever,” I didn’t even own a pair of soccer cleats. But then I spanked them, wearing Converse. I didn’t have a pair of soccer cleats. And when I came off the coach he said to me, “Who are you?” I said, “Well, I came from Newark,” and he said, “Oh you spanked us last year! You’re gonna play for the first team. Where’s your cleats?” I thought, don’t they give their players cleats? Evidently, they didn’t. Guess what, the next day everybody had cleats.

DK: For someone born on the Fourth of July, did you think of yourself much more as an American?

SF: I always thought, I always knew I’d end up here. In the back of my head I always knew I was gonna end up in America. The reason why is I had a grandfather on my father’s side who came here basically at the same age as when I came, back in 1904 or 1906, something like that, and he stayed here all his life, retired from here. He was a master carpenter. He used to come back to Spain and he always used to bring me like a Mets jacket, that kind of stuff, and I always said I had a feeling like we are gonna go. He trained my father back in the 1930s during the Spanish Civil War. But the United States was on the wrong side of the fight. So all the documentation got lost. And it showed up in the early 60s and when it showed up my father didn’t say too much. My father was attached to a boat. He traveled all over the planet. And he loved the States. As soon as he got it, he said, “Let’s go, we’re going to America. Pack it up, we’re out of here.” He went first, and then my brother. And then a couple of years later my other younger brother and I came over.

DK: Your father never got to see you do this, but it is amazing for the son of an immigrant merchant seaman to get into an Ivy League school.

SF: Well, that’s another story, right, another book right there. Listen David, I’m gonna tell you why that happened. I wasn’t supposed to go to Penn. I was recruited from year one. From the moment I stepped on the pitch in high school, I got recruited by everybody. Because I was a little bit more advanced, whatever, it doesn’t matter. But my dream was not that. My dream was going into the military. I wanted to be a flier. So I applied to the academies. I got accepted at West Point, the Naval Academy, and I got accepted to the Air Force Academy. I got accepted to all three of them but I wasn’t a US citizen. So I was only in this country the four years. At that time, I was already on the Olympic team. So I had to rush my papers prior to my fifth year to get my passport, so that I could go with the US Olympic team - I think that year we went to Israel, to Greece and we went to do training there. But I couldn’t go. I wasn’t an American citizen. But through some friends I went to a judge in Newark and they rushed me and somehow, I got my papers. On top of that, we were doing training out in Colorado Springs at the Air Force Academy, and that’s where I wanted to go, because I wanted to be a flier. And they were excited. “Oh my God, this guy is gonna come to the Academy, we’re gonna get a great player blah, blah, blah.” And they said, “Find yourself a school for a year, and then transfer out. Do the year and then you come to us.” I said, “Alright.”

U Penn at the time was #1 in the country. And U Penn at the time, they played on Friday nights under the lights at Franklin Field. They used to get 15,000 people. Research that. When I went there and got recruited, I went in there on a Friday night, I looked at the stands, 15,000, I said, “Yeah, I can see myself playing there, I’d love to play in front of a crowd like that,” and that’s why I went to Penn. That’s how I ended up in Penn and I never transferred out. Once I discovered the Ivy League, once I discovered the country club atmosphere, and who the kids were that I was going to school with, the richest families in America, I said, “To hell with the military.”

DK: But then you walk away from all that into the unknown world of professional soccer in the United States in 1976.

SF: Well, that was sad because my father contracted cancer. He was working at a chemical factory. There was a chemical mischarge and it affected him and he died. He caught cancer of the throat and he died. This was 1974. When you think about it, we were only here for five years. My Mom and my younger brother and I were only here for five years. So I went to Penn in ’73, ’74, then this was going into my third year at Penn. And then we signed Pelé. We signed Pelé and I went, “What? This is serious.” Because at the time I didn’t think the NASL was going anywhere. They were not getting any crowds. They were not getting any attention. It was just a bush league. I didn’t think anything of it, I was just going to school, but then when I saw Pelé coming in I went, “Woah, woah, woah, this changes the whole picture.”

Another incident that I had at Penn that made me go way was I had just come back from the Pan American Games in ‘75 and I had a little incident with the college coach, who thought that it was more important that I stay at Penn and play for Penn than take two weeks off and go represent the United States in Mexico. And that, to me, was like, “Is this guy serious? This guy is telling me to give up my Olympic dream? What does he think Penn is?” But Penn, #1 in the country, you know what I mean? He had a good thing going. But I didn’t even know that freshman year, for example, I could play freshman soccer. I got so ticked off because nobody told me. I terrorized the league. Broke all kinds of records. And so when he told me, “You know, I wish you didn’t go to the Pan American games because we already started preseason and you’re going to miss the first five games,” I thought, “The hell with you.” So, most of my teammates at Penn would have loved to have gone. And that was it, as soon as Pelé came over, ’75. And this was Christmas 1975, going over to 1976, Manfred Schellscheidt was coaching the Hartford Bicentennials. He had been my mentor since I first arrived here. He became a legend - he was my Olympic coach, National Team coach. I looked at him and I said, “Manny, I hate to give you this news but I’m dropping out.” He said, “No, don’t give up school, you’re crazy, you finish your school first.” But I said, “No, Manny, I’m not doing this, I’m going pro. I’m asking, giving you the option first, to bring me in.” Because I was pretty much a free agent. And so he said, “Listen, we’re going to preseason in Germany. I can’t guarantee you anything. You’ve got to earn a spot.” And the rest is history. I just got on a plane with them, went to Germany, and came back. He made me a left back, although I was a center forward. Left wing, center forward. He knew I was, because I played for him for so many years. But he said, “No, I don’t want to put that kind of pressure on you, so you’ll play out of the back.” And I said, “Alright, we’ll do that.”

DK: So that’s where you learned to play left back. I have to ask, on a personal level, Bobby Thomson was a huge influence on me as a kid – he coached me. What was it like to play with Bobby Thomson?

SF: [Laughs] He was okay. I mean, England National Team player, right. But I couldn’t read the Brits. To me they were like a soap car. Although they were world champions in ’66, I played with enough of them, they couldn’t walk and chew gum at the same time. They were just long-ball players that were not comfortable on the ball. Fit as hell. Knew the game backwards and forwards. But when it came to skill, they didn’t have any. And I used to think, “How the hell do these guys play at this level, when the ball is a foreign object to them?” I liked Bobby. He was a nice guy. He ended up becoming my coach.

DK: Of course.

SF: Cause he took over for Manfred and then Bobby was my coach my second year. So there was a little bit of maneuvering and hanky-panky going on, that I don’t want to get into that, because it doesn’t do anybody any good at this stage in the game.

DK: Well, we both have this in common, Santiago: we were both coached by Bobby Thomson.

SF: Well, let’s put it this way: he was my coach but he didn’t coach me. He was my coach but there wasn’t much coaching going on in those days.